When businesses seek to invest in new development they typically perform a cost-benefit analysis as one measure in the decison-making process. In contrast, it is in the nature of academic research that while the costs may be calculable the benefits may be less definable, at least at the outset. When we consider the management of data and outputs emerging from research, particularly in an institutional context such as DataPool at the University of Southampton, we reach a point where the need for cost-benefit analysis once again becomes more acute. In other words, investment on this scale has to be justified.

Ahead of the scaling up of these services institutionally we have enquired about experience of cost-benefits among some of the large research data producers at Southampton, which are likely to be among the earliest and most extensive users of data management services provided institutionally. In addition we have some pointers from a cross-disciplinary survey of imaging and 3D data producers at Southampton, commissioned by DataPool.

Broadly, we have found elaboration of costs and benefits among these producers, but not necessarily together. It has to be recognised that any switch from data management services currently used by these projects to an institutional service is likely to be cost-driven, i.e. can an institution lower the costs of data management and curation?

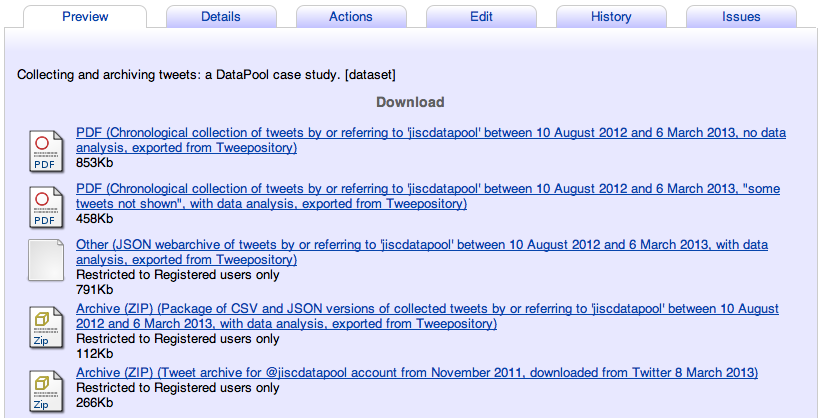

KRDS benefits triangle

eCrystals

First we note that for cost-benefits of curation and preservation of research data a formal methodology has been elaborated and tested: Keeping Research Data Safe (KRDS). This method has been used by one of the data producers consulted here, eCrystals, a data repository managed at Southampton for the National Crystallography Service, which participated in the JISC KRDS projects (Beagrie, et al.):

“This benefits case study on research data preservation was developed from longitudinal cost information held at the Department of Chemistry in Southampton and their experience of data creation costs, preservation and data loss profiled in KRDS”

This case study concludes with a table of great clarity, Stakeholder Benefits in three dimensions, based on the benefits triangle, comparing:

- Direct Benefits vs Indirect Benefits (Costs Avoided)

- Near Term Benefits vs Long-Term Benefits

- Private Benefits vs Public Benefits

μ-VIS Imaging Centre

The μ-VIS Imaging Centre at the University of Southampton has calculated its rate of data production as (Boardman, et al.):

up to 2 TB/day (robotic operation) – 20 GB projections+30 GB reconstruction=50GB in as little as 10-15 minutes

As this data generation and storage facility has grown it has been offered as a service beyond the centre, both within and outside the university. The current mix of users is tentatively estimated at

“10-20% commercial, 10-20% external academic (including collaborative work) and 60-70% internal research.”

This mix of users is relevant as, broadly, users will have a range of data storage centres to choose from. Institutional research data policy at Southampton does not require that data is deposited within Southampton-based services, simply that there is a public record of all research data produced and where it is stored, and a requirement that the services used are ‘durable’ and accessible on demand by other researchers, the latter being a requirement of research funders in the UK. We can envisage, therefore, a series of competitive service providers for research data, from institutions to disciplinary archives, archival organisations, publishers and cloud storage services.

The need to be competitive is real for the μ-VIS service:

“After we went through costings for everything from tape storage through to cloud silos, we noticed that we pretty much can’t use anything exotic without increasing cost, and introducing a new cost for the majority of users would generally reduce the attractiveness of the service.”

Although the emphasis here is on cost, implicitly there is a simple cost-benefit analysis underlying this statement, with possible benefits being traded for lower cost. These tradeoffs can be seen more starkly in the cost-reliablity figures (Boardman, et al.):

- One copy on one hard disk: ~10-20% chance of data loss over 5 years – Approximate cost in 2012: ~$10/TB/year

- Two copies on two separate disks: ~1-4% chance of data loss over 5 years – Approximate cost in 2012: ~$20/TB/year

- “Enterprise” class storage (e.g. NetApp): <1% chance of data loss over 5 years – Approximate cost in 2012: ~$500/TB/year

- Cloud storage. Provides a scalable and reliable option to store data, e.g. Amazon S3 – ‘11 nines’ reliability levels. Typical pricing around $1200/TB/year; additional charges for uploading and downloading

Richard Boardman, Ian Sinclair, Simon Cox, Philippa Reed, Kenji Takeda, Jeremy Frey and Graeme Earl,

Storage and sharing of large 3D imaging datasets, International Conference on 3D Materials Science (3DMS), Seven Springs, PA, USA, July 2012

3D rendering of fatigue damage (from muvis collection)

Imaging and 3D data case study

Image data, including data on three-dimensional objects, are a data type that will be produced across all disciplines of a university. A forthcoming imaging case study report from DataPool (when available will be tagged here) surveys producers of such data at the University of Southampton to examine availability and use of facilities, support and data management. Although this study did not examine cost-benefits specifically, it overlaps with, and reinforces, findings from some of the data producers reported here. Gareth Beale, one of the authors of the study, highlights efficiency gains attributed to accountability, collaboration and sharing, statistical monitoring and planning.

“Research groups with an external client base seem to be much better at managing research data than those which do not perceive this link. This is, we might assume, because of a direct accountability to clients. These groups claimed considerable efficiency savings as a result of improved RDM.

“Equipment sharing between different research groups led to ‘higher level’ collaborations and the sharing of data/resources/teaching. An enhanced researcher and student experience, driven by more efficient use of resources.

“Finally, one group used well archived metadata collected from equipment to monitor use. This allowed them to plan investments in servicing, spare parts and most importantly storage. Estimated archive growth based on these statistics was extremely accurate and allowed for more efficient financial planning.”

Open data

Research data and open data have much in common but are not identical. With research data the funders are increasingly driving towards a presumption of openness, that is, visible to other researchers. While openness is inherent to open data, it goes further in prescribing the data is provided in a format in which it can be mixed and mined by data processing tools.

The Open Data Service at Southampton has pioneered the use of linked open data connecting administrative data and data of all kinds “which isn’t in any way confidential which is of use to our members, visitors, and the public. If we make the data available in a structured way with a license which allows reuse then our members, or anyone else, can build tools on top of it”

While the cost-benefit analysis of data, whether research data or open data, may be similar, there are additional benefits when data is open in this way:

- getting more value out of information you already have

- making the data more visible means people spot (and correct) errors

- helping diverse parts of the organisation use the same codes for things (buildings, research groups)

Linked open data map of University of Southampton’s Highfield campus, from the Open Data Service

Conclusion

The allocation of direct and indirect costs within organisations will often drive actions and decisions in both anticipated but also unforeseen ways. There is ongoing debate about whether the costs of institutional research data management infrastructure should be supported by direct subvention from institutional funds, i.e. an institutional cost, or from project overheads supported by research funders, i.e. a research cost.

Although we do not yet see a single approach to cost-benefits among these data producers, if the result of the debate is to produce intended rather than unforeseen outcomes, it will be necessary to look beyond a purely cost-based analysis to invoke more formal cost-benefit analysis.

I am grateful to Gareth Beale, Richard Boardman, Simon Coles, Chris Gutteridge and Hembo Pagi for their input into this short report.