Institutional research data repositories follow in the wake of the widespread adoption of open access repositories across UK institutions during the last decade. What can these new repositories learn from the experiences of open access, and what pointers can we find for the development of data repositories? In the first part of this post we will consider factors such as policy, infrastructure, workflow and curation. In part 2 we will extend the analysis to rights and user interfaces.

It may be a timely moment to reflect. A recent speech by the UK government’s science minister David Willetts prompted renewed excitement over open access, with a forthcoming report to advise on specific actions to be taken to realise more open access. Less remarked on, apart from comment about the undefined but potentially high-profile role of Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales, was the bigger picture view that anticipates stronger integration and linking between research publications, research information for reporting and assessment, and research data for data mining but also for research testing and validation.

Open access (OA) repositories, which principally provide free access to an author’s version of published research papers, effectively began with the physics arXiv in 1991. Institutional repositories, which switch the focus of coverage from the subject to the place of authorship, emerged in 2001 following the Open Archives Initiative (OAI). To complete the record, the term ‘open access’ was defined by the Budapest Open Access Initiative (BOAI) in 2002.

So institutional OA repositories have up to a decade head start on proposed institutional research data repositories. The University of Southampton, home of the DataPool project, has hosted a leading OA repository since 2005, so the project team has long experience of running a repository.

As with OA repositories, there are plenty of examples of subject-focussed research data repositories, but here we focus on factors affecting institutional repositories (IRs).

Policy

For OA IRs, technology and infrastructure preceded policy. First impressions are that for data IRs this will be the other way round. As with OA, data policies in the UK are being driven both by research funders and institutions.

OA policies focus on the need to expand full-text content collections held in repositories and typically require (mandate) or encourage authors to deposit versions of their published papers. The first university-wide mandatory OA policy was implemented at Queensland University of Technology in Australia, in 2004, according to the site EnablingOpenScholarship. This site also shows graphically how the number of institutional policies began to accelerate from the first quarter of 2009, some 5 years or so since the growth of IRs saw similar acceleration, although it remains a minority of institutions that have such polices. It has been calculated that OA mandate policies can increase deposit rates to above 60% of eligible papers from the average of 20%. In this respect, the lack of a suitable policy could be seen to hinder an institutional OA repository.

Emerging UK institutional data polices by comparison have focussed on requiring researchers to create data management plans and data records, and emphasise sustainable practices in managing and storing data for the purpose of access, stopping short of requiring open access or of institutional deposit of actual data that would then need to be supported by the institution. This might be because institutions have still to calculate and cost the the storage infrastructure needed, whether managed locally or in the ‘cloud’, because institutions are unclear what value they can bring to data management – or even where the value is in the data they seek to help support, or because there is not yet any consensus on whether data repositories should be subject-based, or institutional, an issue which OA repositories have still not fully resolved. Institutional data policies have in turn been driven and directed by research funders’ data policies, principally RCUK and EPSRC (Jones 2012) setting principles and expectations of institutional compliance within a specified timescale (for EPSRC, by 2015).

Data policies may benefit from being instituted ahead of developing infrastructure for collecting, managing and presenting data. However, the few early policies available suggest little common purpose – we are clearly some way from having a best-practice data policy template for others to follow, as has evolved for OA repositories. To serve even the limited requirements of these early policies, institutions will need to connect decisions on infrastructure and understand patterns of workflow that produce research data, as we shall see below.

Infrastructure

By infrastructure we mean the technical capability to support distinctive requirements. While OA repository infrastructure is well established, it has not had to tackle the challenge of large-scale storage that is likely characterise data repositories.

The essential infrastructure that led to OA repositories was put in place by OAI: this was a protocol for metadata harvesting OAI-PMH. This allowed individual repositories to be viewed collectively through services – search being the most prominent service, at a time when Google was new and relatively little known – based on OAI-PMH. Immediately, software emerged for setting up institutional repositories, first EPrints and later DSpace and others. These repository softwares now also bring a range of integral services established over a decade that can be utilised to manage a range of data types, including research data.

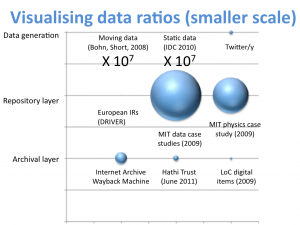

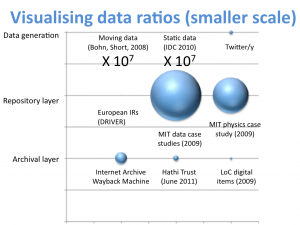

Hence this same infrastructure, with modification, is being used to serve data repositories. There is, however, one new infrastructure component that data repositories will need to introduce – large-scale data storage. While content volumes for OA repositories do not test conventional storage systems, data repositories will inevitably provide much bigger challenges to storage and curation. To get a sense of the scale of the problem, Figure 1 compares data volumes at different stages, and is taken from a presentation about scoping curation for digital repositories. It is notable that data generation volumes cannot be visualised on the same scale as the other stages, since these are orders of magnitude larger. We might call this the data curation gap. Rosenthal has recently questioned assumptions that all data generated might be kept ‘forever’, indicating the need to fill the curation gap: “Assuming (data) growth continues, endowing 2012’s data will consume 19% of Gross World Product (GWP). On these trends, endowing 2018’s data will consume more than the entire GWP for the year.”

Figure 1. Comparing data volumes at different stages - generation, repository storage and archiving

Institutions appear to have two choices to serve this level of storage: locally managed, or remote storage in the cloud. It is likely there will be a preference or a requirement to exert institutional control over storage (for example, at the University of Brighton: “we currently have a policy of not hosting staff data outside of the institution”), even in the case of cloud storage, hence developments such as the JISC UMF Cloud Pilot managed by Eduserv.

They could instead opt to advise researchers and data producers on selecting their own storage, from data archiving services such as UK Data Archive and the Archaeology Data Service, or data publication repositories such as Figshare, Dryad and other data repositories listed by DataCite, or even commercial cloud storage services (although a colleague noted that risk-averse advice might wish to start with where not to store data). Apart from the data archiving services, it remains to be seen whether these repositories can provide resilient, cost-effective, sustainable storage over an extended period, where content can be shared collaboratively during development and later made open access.

Workflow

OA repositories were designed from the outset for a publication mode of delivery that does not attempt to capture and support earlier phases in the workflow of writing a research paper. Given the more complex workflow (or life cycle) of research data, and the need to capture data at different stages of production and processing, the single publication mode may be inadequate for data repositories.

As the Web gained popularity in the mid-1990s all sorts of content began to appear, including digital versions of research papers published in what were then still largely paper journals. Authors were simply loading digital versions on to Web servers wherever these happened to be available, usually within their institutions, whether these servers were provided for this purpose or not.

OA institutional repositories served a simple purpose – to provide these authors with a more reliable, managed, services-based Web server to provide access to this digital content over a long timeframe. In this respect the designers behind these repositories over-estimated the number of authors that would use such services and the number of papers that would appear in repositories. Further, because the target content was papers due for peer-reviewed publication, the concept of workflow was barely considered beyond the expectation that the process of repository deposit would happen at the completion of writing the paper and in parallel with submission for formal publication. Thus OA repositories were designed for a one-stage deposit workflow, and no prior contact with authors while a paper was in preparation.

It has been suggested that by failing to engage authors at a sufficiently early stage and not providing support services for writing papers, that OA repositories have lost out to the more established process at the completion of a paper – publication. Further, by the time IRs were widespread, most journals were producing digital versions, so that was no longer a factor for authors posting Web copies of their papers, even if those journal digital versions still mostly stood behind subscription barriers.

While it is in principle simple to upload a completed paper from a local file store to a repository, it has been argued that a restraint to this happening is the requirement by many repositories for extensive accompanying ‘keystrokes’ or metadata. Competition with publishers for keystrokes at the point of completion and submission, lack of clarity in the benefits of OA repositories, and the failure to integrate with workflow may have been factors in preventing OA repositories from growing content to the levels anticipated, and led directly to the mandate policies described above.

The lesson for data repositories is clear: to capture content from data creators you must provide useful services that will become an integral part of the workflow of creating the data. It will not work to isolate particular requirements, such as records creation, from other needs such as storage services. Data does not appear with the same mode and frequency as published papers, so workflow must accommodate many different patterns. Research data is often produced by machines, so deposit workflow must allow scope for non-manual intervention.

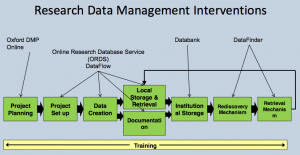

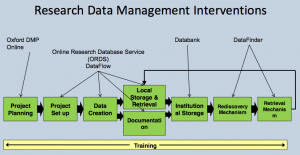

While workflow involved in the production of research data is more complex and less easy to classify than for OA publications, one helpful representation of this workflow has been illustrated by the University of Oxford (Figure 2). This shows how a project begins with a bid for funding and in future will invariably be accompanied by a data management plan (DMP), a data roadmap for the project to follow. If a workflow begins with a successful proposal and a DMP, it will lead to data and, increasingly, from policy or from users, a requirement for managed data storage with the ability to support controlled access for collaboration, and discovery for wider access. Figure 2 is taken from this presentation by the DataFlow Project.

Figure 2. Representation of a research data management workflow, from the University of Oxford

Effective institutional data services will need to span this whole workflow and engage data creators at all stages. Lessons on workflow from open access suggest that for research data providing separate services for creating data records and storage, for example, will be insufficient. Data creators and authors will not engage in processes that do not enhance their work.

Curation

Digital curation is defined by Wikipedia as the “selection, preservation, maintenance, collection and archiving of digital assets”. For open access, selection is pre-determined – the target content is peer reviewed and published research papers. Further selection of such content for curation purposes is not merited by the data volumes involved. As we have seen with the ‘curation gap’ above, this does not hold for research data. As a result, more attention will need to be paid to curation for research data, and the line between simple user-managed storage and assisted curation will need to be more flexible.

Where that line might be drawn is thus open to question. It is drawn in principle by the strategy exemplified by DataFlow in Figure 2, which has two stages representing user-managed workspace and storage (the stage to Local Storage & Retrieval in Figure 2), with a transition to an institutionally curated space (Institutional Storage, or DataBank in Oxford’s system). The question remains as to what drives that transition. Such spaces are likely to have different curation criteria in different institutions, and will need to take account of researcher, policy and publication requirements, as well as costs.

An example of research data management that has optimised workflow, metadata collection and records creation, data curation, aggregation, discovery and access is eCrystals at Southampton, now extended to a federation led by the UK National Crystallography Service.

Interim summary

There are more lessons to learn from experience with open access that we can apply to research data repositories. In part 2 we will extend the analysis to rights and user interfaces.